Article translated by an automatic translation system. Press here for further information.

Silver Way

26

704,6

The Silver Way

Perhaps it is a matter of time, but if Google Earth software could apply its powerful zoom, not only to any country, but also to any time in history, we could go back to year 196 BC and see clearly the limits and extent of the provinces Citerior and Posterior, the germ of what is now Spain. It was twenty years since the Romans had landed on the peninsula and not only managed to bend and expel the Carthaginians, but also planned to order a jigsaw of over half a million square kilometres consisting of tribes of astures, Cantabrians, Celtibers, Galatians, Lusitans, Turdetans, vacancies, Vascones, Vetts and a long line of peoples clinging to their land. In short, a puzzle with thousands of scattered pieces that the Roman army managed to unite in 19th B.C. after more than a century and a half of bloody wars. In this long period of change the terms Citerior and Subsequent disappeared and Hispania became divided into the provinces Tarraconense, Bética and Lusitania. The Iberian peninsula was finally under the power of Rome and the times of the republic had ended at the hands of Octavio Augusto (63 BC–14 AD), who had proclaimed emperor.

Roman roads in Hispania and its construction cenit in imperial times

Millennia before the arrival of the Roman Army, there were already countless paths, paths or roads drawn by the pre-Roman peoples and linked mainly to their grazing and livestock transit tasks. There is no doubt that the Roman army took advantage of and improved these rough roads to move forward more quickly in its task of conquest. However, during the war it was useless to embellish the roads too much because of the shortage of time and the fear that they would be used against them by Hispanic warriors. With the end of the conflict and the arrival of peace, Roman civilization began to manifest in Hispania its political, administrative, artistic and constructive skills. In the first centuries of our era, until the invasion of the barbaric hordes in 409 A.D., the physiognomy of the peninsula changed radically and the Celtic castros fell before magnificent cities equipped with forums, theatres, amphitheatres and baths. All a luxury for the sake of coexistence and enjoyment of the Roman citizen. Among them, in addition to the solid and still bridges mark the house, the Roman engineers built an extensive network of roads that communicated Hispania from north to south and from east to west.

Roman engineers and workers used the materials they had most at hand for their roads and built them based on the four-layer agglomeration. The statumen was based on a sand base, a first layer composed of small stones that joined with lime or clay. Upon it was cast the rudus, a powerful mass of stones and pebbles sealed with lime mortar. The third layer was the nucleus, pure coarse sand concrete, and the last of all was the visible tread layer or crest summa, formed by the typical stone sanding. In this regard, Isaac Moreno Gallo, in his study Vía Romanas, Ingeniería y Técnica Constructiva published by the Ministerio de Fomento, defended that the tread layer was not enlarged but that on the slabs there was another thinner layer of loose soil that allowed cars to move forward at a faster rate.

Next to the roads there were some distance indicators called miliaries that were placed every 1480 meters. This measure was the length of a Roman mile and was equivalent to a thousand Roman double steps, considering that each double step measured one meter and forty-eight centimeters. The miliaries are cylindrical columns of granite engraved, in addition to the mile number, the name of the emperor he sent when the roads were built or modified. In the Silver Way many of them still persist, and in particular numbers XXVIII and CXXXIV are known as miliary of the Correo and miliary of the Corral.

The Antonino Itinerary:

This name refers to a map of Roman roads of 217 AD that was later transmitted through codices. The map in question has been the best and most complete legacy that has allowed to know the whole network of roads that emerged in Hispania in the imperial era. The Itinerary records in our peninsula 34 different routes and provides data on the miles of each and their mansios, a kind of inn that served as a place of rest for travellers and to supply the chivalry with other refreshments.

The Silver Way:

By this name is known the Roman road departing from Emérita Augusta, capital of the Lusitania and current city of Mérida and reaching Asturica Augusta, the Astorga today. In the Antonino Itinerary this route would be equivalent to the XXIV road between Mérida and Zamora and the XXVI between Zamora and Astorga. It was traced during the Roman invasion at the end of the 1st century BC for a purely military purpose and became a commercial network during the centuries of the Empire.

The nickname of Plata remains a mystery and the most widespread opinion defended by professor José Manuel Roldán Hervás in his work Iter Ab Emerita Asturicam, El Camino de la Plata, published in 1971 by the University of Salamanca. According to Roldán Hervás the name of silver derives from the Arabic word BaLaTa, which means loosen, and it reads as follows: "Even today, in Syria, it is known under the name of BaLaTa, the path that appears enlarged with irregular and large stones, so we believe that we are quite close to reality if we think that the people took the strange sound of the Arabic and made it their own in the Castilian homophone word that was closest to them and that was obviously silver."

Pilgrimage through the Silver Way:

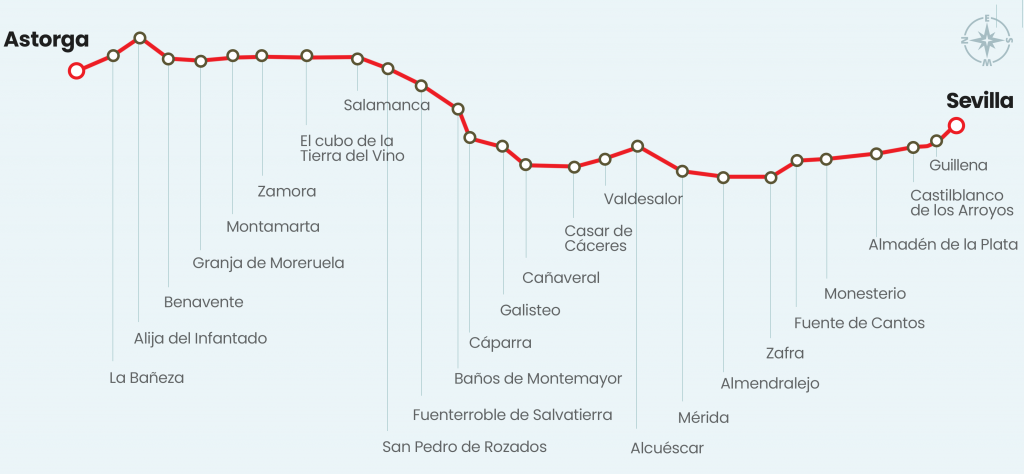

There are hardly any senderists who are merely content to discover the Roman legacy through the 490 kilometres between Merida and Astorga. The Silver Way, the main axis of communication of the Spanish West, became the Jacobean route of the South and today is the route chosen year after year by over 4,000 pilgrims to reach Santiago de Compostela. Due to a shortage of time some start in Merida, but the vast majority of them go from Seville and follow the route of the Roman Way to Granja de Moreruela, the Zamorana town where they catch the diversion of the Sanabrés way that takes them after thirteen more days to Santiago. The least continue along the Silver Way to Astorga to link to the French Way.

The Silver Way is the kingdom of the yellow arrow. The old Roman slabs have given way to the Chilean painting brands and they are the best ally to avoid getting lost between hesas and piste resettlement. The arrows are spread throughout the entire route and, moreover, throughout Extremadura there are some granite cubes baptized with the name of H1 that highlight the arc of Cáparra. If they show a yellow tile, they indicate that the road is transitable, although it does not coincide with the original route. If the mark is green, follow the route of the millennium road, and if both coincide the road is transitable and follow the path that the road had. The yellow arrows and the Jacobean route match the cubes that show yellow tile or green-yellow tile.

From Seville to Astorga there are 705 kilometers and the route, which had 20 mansios, follows the four-way route of the Antonino Itinerary:

Number IX, Ab Hispali Italicam, the shortest of the road network and that communicated Seville with Itálica, the current Santiponce.

The number XXIII, Item ab ostio fluminis Anae Emeritam used which united Ayamonte, in the mouth of the Guadiana River, with Mérida. The pilgrim takes the itinerary of this road in Santiponce and continues through its surroundings to Mérida, passing through the localities of Castilblanco de los Arroyos, Almadén de la Plata, El Real de la Jara, Monesterio, Fuente de Cantos, Zafra, Villafranca de los Barros and Torremejía.

The number XXIV, Item ab Emerita Caesaraugustam, linked Mérida with Zaragoza. It is followed from Merida to Zamora, from the Guadiana River to the Douro.

The XXVI, Item ab Asturica Caesaraugustam, joined Astorga with Zaragoza and went through Zamora, a city where it was taken to reach Astorga, the end of the Silver Way.

Bibliography:

Iter ab Emerita Asturicam: the Camino de la Plata, written by José Manuel Roldán Hervás and edited in 1971 by Ediciones Universidad de Salamanca.

Repertoire of Caminos de la Hispania Romana, written and edited by Gonzalo Arias in 1987.

Roman Roads, Engineering and Construction Technique, written by Isaac Moreno Gallo and published in 2004 by the Ministry of Development.

The adventure of the Romans in Hispania, edited by The Book Sphere in 2005.